Dipak Patel can still recall the dizzying grandeur of his 2003 visit to Beijing’s cavernous Great Hall of the People: the rows of stern guards all the same height, the state dinner that included stewed shark fin and bird’s nest soup, and the People’s Liberation Army band playing songs from Patel’s native Zambia—even singing in one of the African country’s scores of dialects.

As Zambia’s minister of commerce at the time, Patel had joined the delegation to cement ties and—crucially—secure financing for big-ticket infrastructure initiatives. While most delegates were eager to accept anything they could get for projects such as a hydropower dam and a 50,000-seat soccer stadium, Patel urged caution. “My view was that we needed to build a strategic partnership and think it through,” he says. “But I was one voice in the cabinet.”

His warning went unheeded, and Zambia started to take out loans from Chinese banks for airports, hospitals, housing projects, and the roads connecting them. Chinese credit has grown to about a third of Zambia’s external debt, which has surged sevenfold over the past decade, forcing the government this year to ask creditors to reschedule loans. Patel, now a real estate investor, is challenging in court the legality of billions in foreign money Zambia has borrowed without what he says was required consent from Parliament. “Nobody other than the government knows the terms,” he says. The government says it didn’t need parliamentary approval.

Patel is among a growing number of African activists and policymakers questioning the deluge of Chinese credit—some $150 billion in 2018, according to researchers at Johns Hopkins University—that has fueled a debt crisis aggravated by the new coronavirus. Nigerian lawmakers are reviewing Chinese loans they say were unfavorable. Activists in Kenya are demanding the government disclose the terms of Chinese credit used to build a 470-kilometer (292-mile) railway. And Tanzanian President John Magufuli calls an agreement his predecessor made with Chinese investors, to build a $10 billion port and economic zone, a deal “only a madman would sign.”

While it will be tough for cash-starved African governments to win many concessions, a wave of looming defaults poses the biggest test ever for China’s influence in the region. “This has the potential to produce the most profound change in relations since China became a major economic player on the continent,” says Chris Alden, an international affairs professor at the London School of Economics. “African governments and society are increasingly asking China to come up with answers to this problem.”

In Africa, Beijing was eager to fill the vacuum left when U.S. and European interest in the continent waned following the end of the Cold War. Governments there were hungry for loans not tied to austerity programs imposed by Western financial institutions, and China was quick to approve credit, with scant concern about the money going to regimes accused of corruption or human-rights violations. “For China, as the newest power on the block, the only region of the world that was uncontested was Africa,” says Gyude Moore, Liberia’s former minister of public works and now a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development in Washington. “When people complain about Chinese loans, it’s not as if most African countries have a plethora of options.”

It’s hard to miss China’s footprint in Africa. In tiny Guinea-Bissau, the exit signs in a government building are written in Chinese characters. In Mozambique, Chinese money paid for a 2-mile-long suspension bridge, the longest on the continent, that links the capital with beach resorts and neighboring South Africa. China helped foot the bill for Senegal’s Museum of Black Civilizations—which until recently included Chinese art in its exhibits. It’s become the largest financier of infrastructure in Africa, with the likes of the China Export-Import Bank and the China Development Bank funding a fifth of big projects, according to consulting firm Deloitte. To guarantee a quarter of that debt, African countries have effectively mortgaged future earnings from exports of commodities such as oil, cocoa, and copper.

While loans by private investors from around the world still make up more than half of Africa’s external public debt, Germany’s Kiel Institute for the World Economy says China has lent more than the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the Club of Paris, a group of wealthy countries, combined. And many loans aren’t made public, prompting suspicions that Africa’s debt to China is bigger than estimated. The Kiel group says as much as half of all Chinese lending to developing countries, or about $200 billion, hadn’t been reported to the IMF and World Bank as of 2016. The Chinese loans have drawn parallels to the lending boom of the 1970s that led to a crippling debt crisis across the developing world a decade later. “We’ll see a wave of defaults,” says Christoph Trebesch, an author of the Kiel study. “It’s just a question of whether it will be a huge wave or a small wave.”

Nondisclosure clauses mean many loans escape public scrutiny, raising fears of money ending up in the pockets of corrupt officials or middlemen. A Hong Kong businessman known as Sam Pa (he has at least seven aliases), believed to have brokered various multibillion-dollar deals in Africa, was detained in 2015 as part of an anticorruption campaign in China. Pa’s opaque business empire, in part financed by Chinese state-run banks, is still being unwound by prosecutors. “If there is so much secrecy around Chinese lending, there must be something illegal,” says Khelef Khalifa, an activist demanding the Kenyan government provide details on debt from China used to fund a rail link from the port of Mombasa to the capital, Nairobi.

The Trump administration has accused China of loading poor countries with unpayable debt to snatch up prized assets and boost its clout with vulnerable governments. But some researchers say fears of Chinese predatory lending are exaggerated. China hasn’t seized property or used courts to enforce debt payments, according to a study by the China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins. The study’s authors say the most frequently cited example of what awaits developing countries that default on Chinese loans—Sri Lanka’s sale of a majority stake in a port to a Chinese company in 2017—was a privatization and not a debt-for-equity swap as reported by some media.

Faced with growing criticism and a slowing economy, China has become more cautious. Its multibillion-dollar “Belt and Road” initiative, aimed at expanding commercial ties around the world, has tightened oversight of projects and it now gauges a country’s capacity to repay before approving credit. Annual loan commitments have fallen from a peak of almost $30 billion in 2016 to $8.9 billion in 2018, Johns Hopkins says. Chinese President Xi Jinping has vowed to cancel a small portion of loans to governments in Africa and called on state-run banks to rework commercial debt owed by borrowers in the region. Debt service on Chinese lending accounts for 60% of all bilateral debt principal and interest payments due this year from the 73 countries eligible for an eight-month suspension offered by the Group of 20 leading economies, the World Bank says.

It may be easier for African countries to gain debt relief from China than from commercial bondholders, according to Deborah Brautigam, who co-authored the Johns Hopkins study, which examined more than 1,000 Chinese loans to the continent. While private investors have sued countries over defaults and workouts can entail years of negotiations, Chinese lenders don’t have a lot of leverage over borrowers, and there’s little evidence of penalties for nonpayment. China has written off $3.4 billion and restructured or refinanced about $15 billion of debt in Africa over the past decade, Brautigam says. “We don’t see a lot of options for Chinese lenders,” she says. “They can’t send in gunboats.”

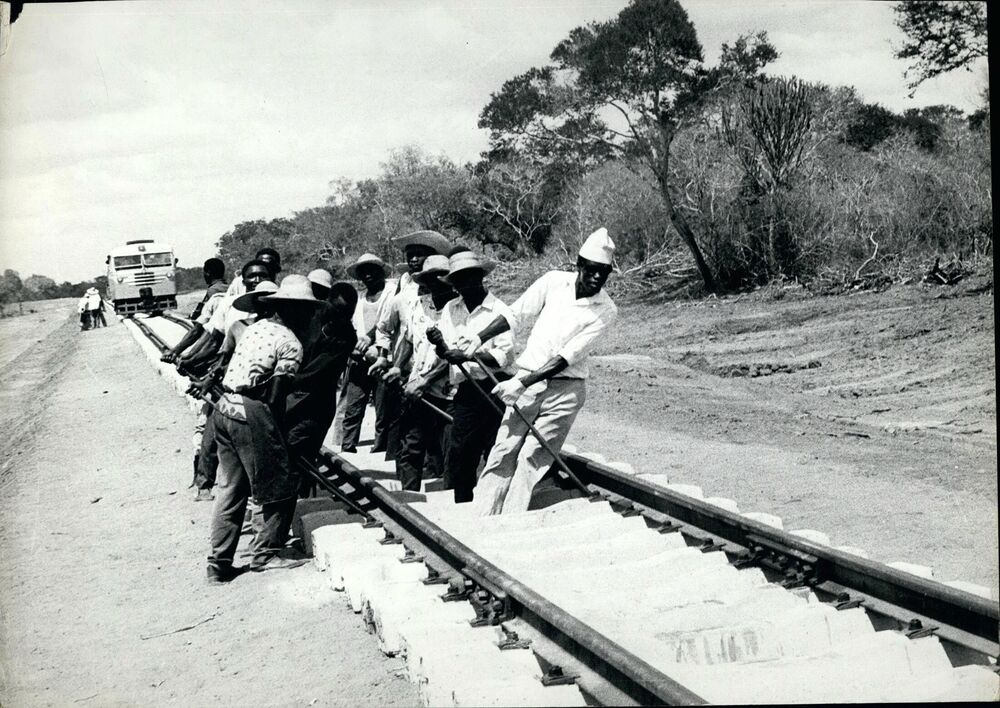

Even with some relief, Africa, facing its worst recession ever and with few other sources for fresh loans, will likely remain deeply indebted to China for decades. Zambia still hasn’t paid off the Mao-era Tazara railway, a 1,860-kilometer line built in the 1970s to haul copper to the port of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. The railway, China’s first foreign aid project—intended to circumvent White minority-ruled Rhodesia and South Africa—is in deep disrepair, operating at a fraction of its original capacity, with few working locomotives. That, says Patel, the former Zambian minister, should serve as a note of caution, as the railway never met its goals and paid back on the investment. “You would have thought the government would have learned from that lesson,” he says. “If you borrow for projects that have hardly any economic return, then it becomes a liability.”

Bloomberg