Almost two decades of profligate monetary policy has destroyed Zimbabwe’s economy and fueled rampant inflation, decimating the savings of its people twice.

Hyperinflation of as much as 500 billion percent in 2008 made savings worthless and led to the abolition of the local currency in favor of the dollar the following year. In 2016, former President Robert Mugabe’s cash-strapped government introduced securities known as bond notes that it insisted traded at par with the dollar. In 2018, it separated cash from electronic deposits in banks without reserves to back them, causing the black-market rate to plunge.

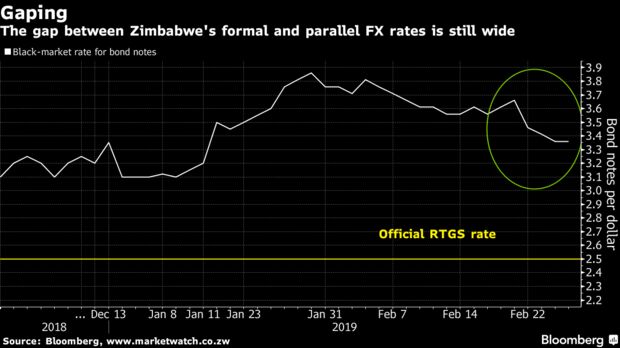

Last week, it threw in the towel and allowed bond notes to trade at a market-determined level, once again slashing the value of savings. The decision came after the southern African nation faced shortages of bread and fuel, was hit by strikes and protests, and President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s drive to attract new investment floundered.

“At the root of this is the currency crisis,” said Derek Matyszak, a Zimbabwe-based research consultant for South Africa’s Institute for Security Studies. “This is analogous to them creating a giant Ponzi scheme that originated under Mugabe. What we are seeing now is that Ponzi scheme collapsing.”

‘1-to-1 Fiction’

The latest step, while welcomed by what’s left of the country’s business sector, is unlikely to solve Zimbabwe’s problems because all it does is reflect exchange rates on the black market, according to Steve H. Hanke, a professor of applied economics at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

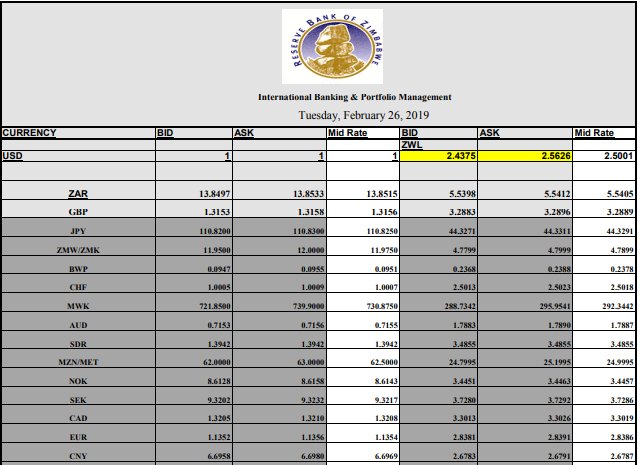

The interbank rate for the new currency is about 2.5 to the dollar, data published on the central bank’s website shows. That figure is meaningless because the authorities are failing to divulge the volume of trade, according to marketwatch.co.zw, a website run by financial analysts. It estimates the black-market rate for the bond notes is 3.36 per dollar.

The origins of Zimbabwe’s currency crisis stretch back to a violent land-reform program initiated by Mugabe in 2000, which slashed export income and devastated government finances.

In response, then-Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe Governor Gideon Gono, known as ‘God’s banker’ because of his close ties to Mugabe, increased printing of Zimbabwe dollars exponentially to pay government workers, stoking inflation and eventually making the currency valueless.

Printing Money

“It was a Ponzi scheme in the past,” said Ashok Chakravarti, an economist and lecturer at the University of Zimbabwe. “Especially in the Gono era, where that chap just kept printing money.” Gono didn’t answer a call to a mobile phone number he has used in the past.

The currency’s collapse led to the predicament Zimbabwe now finds itself in — chronic cash shortages and rampant inflation.

By late 2008, some Zimbabweans had reverted to barter trade as illicit dealings in foreign currencies flourished. In February 2009, the answer the government came up with was to switch to the use of foreign currencies, mainly the U.S. dollar.

“Dollarization puts a hard budget constraint on the system,” said Hanke. “You can’t go to the central bank or any other government institution to get credit for the government.”

Repaying Debt

The pressure on government finances led to history repeating itself, with a loophole being found: the introduction of bond notes and locally denominated electronic money. That contributed to money in circulation growing to more than $10 billion, according to George Guvamatanga, the permanent secretary in the Finance Ministry. The figure was $6.2 billion in 2013, said Tendai Biti, a senior opposition leader and former finance minister.

“If you continue to print money you are destroying what you are creating,” Guvamatanga said. Under a stabilization program introduced by Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube in October, the government is now repaying domestic debt, has stopped issuing Treasury bills and has no overdraft with the central bank.

That’s helped the economy move toward “walking on two legs, there is an effort to go in a different direction. It’s an inevitable adjustment.”” Chakravarti said. “It’s very unfortunate that this is the second time in 10 years people have lost the value of their savings. In 2009 we all went down to zero including me.”

For some observers the latest development isn’t a sudden discovery of fiscal discipline. It’s another admission of failure and the victims are Zimbabwe’s people.

Zero Savings

To Biti, who says the new currency will fail because it isn’t backed by reserves, it shows the country has come full circle.

“It’s theft because people had regrouped and rebuilt their lives from zero based on the U.S. dollar,” he said.

The country’s best hope is to join southern Africa’s Common Monetary Area, which is dominated by South Africa and its rand, Biti said. That would give certainty to business and impose fiscal discipline on the government, as opposed to the current arrangements that are unsustainable, he said.

“It’s a Ponzi economy,” he said.

Bloomberg