A plunging oil price gives African central banks more to think about as they move toward a cycle of raising interest rates.

With a month to go before the U.S. Federal Reserve delivers what would be its fourth interest-rate increase of the year, African policy makers may still move to tighten to avoid a further sell-off of assets and currency weakness. Oil importers will see reduced pressure on inflation as fuel prices moderate, while those that export could see more inflation if their currencies drop.

Central bankers in Nigeria, South Africa and Zambia may follow Uganda’s lead this week and start tightening. Officials in Ghana and Kenya will likely stay put for now.

Until the crude price-plunge, “for most African countries it seemed that policy would be tighter for longer, but if oil prices continue to fall, given that it is such a large part of most countries’ imports profile, inflation would follow and the bias could eventually shift,” said Samantha Singh, an analyst Absa Group Ltd. in Johannesburg. But for producers, “the drop in oil prices could cause foreign-exchange supply challenges, which could be inflationary,” she said.

Zambia

Zambia’s kwacha has depreciated more than 3 percent against the dollar in 2018, helping to drive inflation to an almost two-year high in October. This could trigger an upward move in the key rate from 9.75 percent on Wednesday.

Nigeria

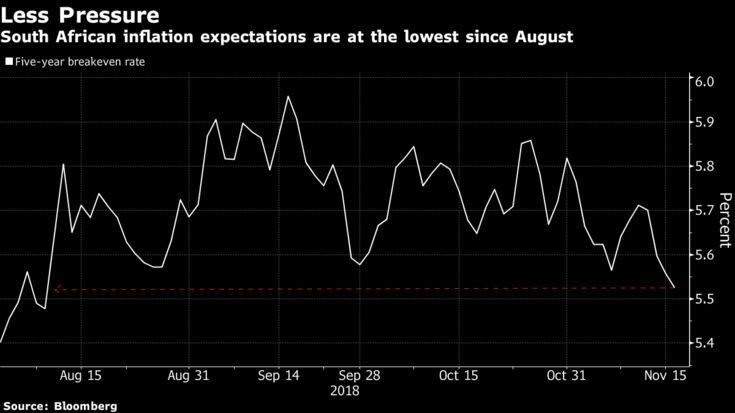

South Africa

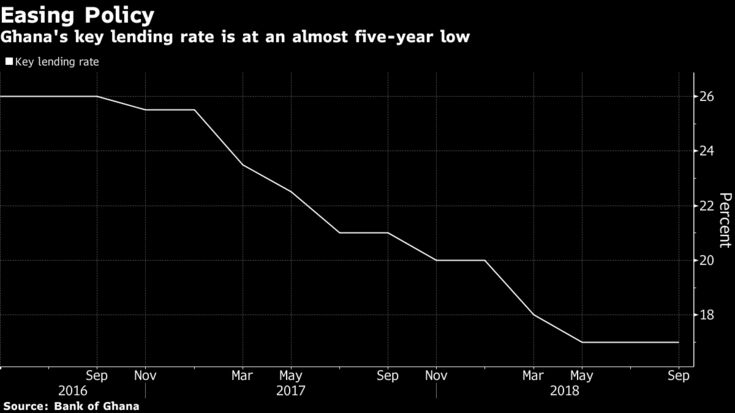

Ghana

Despite a slowdown in inflation and an improvement in the cedi, the MPC “cannot get too excited and too bullish,” said Courage Boti, an Accra-based economist at Databank Group. “Caution is the primary reason why the policy rate will be held. The MPC must be sure that the improvements

are consolidated and overturns any potential elevation in inflation expectations.”

Kenya

Angola

Angola’s inflation rate declined to 17 percent in October from as high as 42 percent in December 2016 even as the kwanza weakened the most among currencies on the continent following a devaluation. With limited transmission from lening costs to price growth, a Bloomberg survey shows the central bank could cut its key rate to help boost an economy that’s forecast to contract for a third consecutive year in 2018.